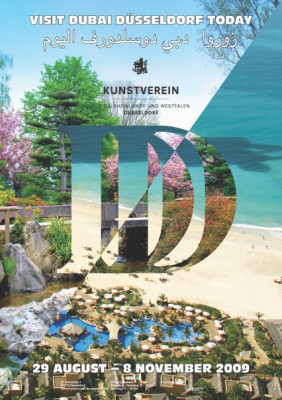

Dubai Düsseldorf

Kunstverein Düsseldorf

2009

Düsseldorf, DE

Commissioned by Vanessa Joan Müller

Group Exhibition with contributions by Ayzit Bostan, Zak Kyes, Antje Majewski, Markus Miessen, Eva Munz, Ralf Pflugfelder, as well as Ingo Niermann, Peter Maximowitsch & Stephan Trüby.

Catalogue with contributions by Shumon Basar, Carson Chan, Zak Kyes, Holger Liebs, Antje Majewski, Markus Miessen & Ralf Pflugfelder, Eva Munz as well as Ingo Niermann, Peter Maximowitsch & Stephan Trüby.

- Architectural design and spatial contributions by Markus Miessen and Ralf Plugfelder

- Curated by Ingo Niermann

- Catalogue Design and photography by Zak Kyes

For the last years, Dubai's ruler, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, has pursued a simple goal: to become number one in everything. Dubai would get the world's biggest cargo port, the world's tallest skyscraper, the world's largest airport, the world's biggest amusement park, and the world's greatest concentration of five-star hotels. But in May 2007, Head of Dubai's Road and Transport Authority, Matter Al Tayer, asked at the International Design Forum about the emirate's growing traffic problems, found these astonishing words: "I love Düsseldorf. It's my favourite city. With bicycles and pedestrian zones next to the Kö [the Königsallee, a central boulevard and luxury shopping mile]."

Düsseldorf was one of the pillars of the German economic miracle of the fifties; with the Kö, the high-rise building popularly called Dreischeibenhaus ("Three-Slice Building"), and its pedestrian traffic lights featuring a yellow phase, it came to epitomize German modernity. Today, Düsseldorf is wealthier than the average German city, but since the reunification of Germany, it has largely failed to attract attention on the supraregional stage. With the end of the real estate boom and the onset of the global financial crisis, Dubai, for its part, finds itself buried under a gigantic load of debt.

What if, in this era of globalization, not only corporations from different countries and continents merged but cities as well? Which synergies might such a fusion generate? Which imaginations and energies might the mere announcement unleash? Starting from an idea proposed by architect Markus Miessen and writer Ingo Niermann, a team of artists, film directors, designers, and architects speculated about how Dubai and Düsseldorf unite their strengths to find solutions for the 21st century.

Future Perfect Continuous

By Carson Chan

As the Bank of England’s ‘Architect and Purveyor’ from 1788 until his retirement in 1833, Sir John Soane saw to the completion and continual implementation of the bank’s neo-Classical design, which stood intact until it was finally rebuilt to Herbert Baker’s specifications between the wars. Soane, whose famous obsession with the trappings of man’s endeavor against the wheels of time (sarcophagi, busts, oil paintings etc.), propelled him to not only collect from the past, but to project the future of history – as if doing so would bring even the uncertainties of tomorrow into his control. In Crude Hints towards the History of My House, a text he wrote in his sixties, Soane imagined returning to his London home (now a museum) at Lincoln’s Inn Fields two-decades later, to find it a ruin. In 1830, the year of the fictional homecoming, Soane commissioned his amanuensis-turned-creative partner, Joseph Gandy, to make perspective renderings of the Bank of England. As in Crude Hints, Gandy’s softly luminous images show the bank building overgrown and dilapidated – its front steps on Threadneedle Street drop into a rocky chasm.

Architecture, shown through pictures, is conducive to this sort of storytelling. Narrative images - done in atmospheric perspective – have allowed Bible stories and property-developer pitches verisimilitude. What is obvious in Markus Miessen and Ralf Pflugfelder’s fanciful Dubai/Düsseldorf alliance – where images are deployed in such a way – is that beyond spinning an architectural fiction, the architects also employ narrative pictures as the metric against which lived reality is observed, critiqued and calibrated. Giving these places a future narrative is to look at them away from historical and political distractions, where meaning can fall anew onto known forms.

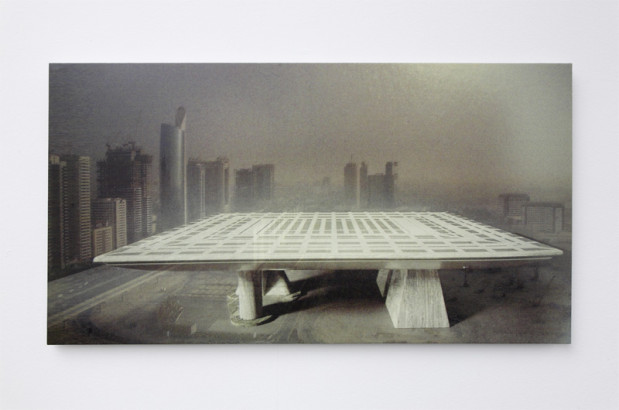

Miessen and Plugfelder’s Kunsthalle Dubai Düsseldorf project (2009), a collection of two and three-dimensional representations of fictional architecture projects in each of the two places, begin its narrative in 2008 when the global economic crisis seizes the local coffers and moves them into a partnership that would ensure mutual wealth and business opportunities. As if the bane of one is the boon of the other, the twinned governments ban art to save the economy – clueing in to the fact that the billions spent on art each year have offset available monies for far more dire global pursuits, say, green energy or world hunger. Art, it can be said, becomes detrimental to culture.

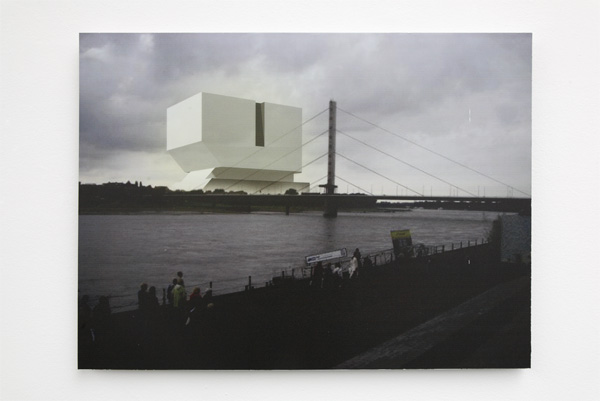

To mark this shift, like all past monumental paradigmatic shifts, two colossal structures are built, one in each town, to display a single piece of art – the only, and last allowable art-object, commissioned to commemorate the momentous union. The Kunsthallen are hollow, identical, chamfered boxes, like oversized John McCracken sculptures with about seven times more floor space than the Louvre. In Düsseldorf, the building sits on a plinth overlooking the Rhine. In Dubai, its height, 450 meters, is sunk into the ground – ostensibly to counter the emirate’s punishing climate and density. The structure’s interior walls are lined with terraces that allow visitors to view the single art-object, enshrined and ceremoniously lifted on a plinth.

The Kunsthallen play foil to Boulée’s 18th century, totalizing, encapsulations of knowledge with which they share iconic stature. Where the Bibliothèque du Roi (1785) or even the Cénotaph à Newton (1784, and roughly the same height as the Kunsthallen) bear the imprimatur of Empiricism, and therefore a hermeneutics of endless deducibility, the Kunsthallen sits vacant, and silently delays interpretation of its use or purpose. If Boulée’s designs depict the apotheosis of human learning – taking form as cosmic globes, cloud-piercing pyramids and bookshelves that recede into the horizon – it also exposes its limitations in the absolute finitude of materiality. A library, no matter how long its shelves, contains a limited number of books – a sobering concept contra to the suggestion of a roving, ever-expanding ken.

If Boulée’s architecture lays out a rational directive, then the Kunsthallen run on parallel but opposite passions, and in Miessen and Plugfelder’s chonology (the buildings are completed in 2071), they act as proverbial bookend to the Enlightenment shelf. By putting almost nothing inside their vacuous spaces, Miessen and Pflugfelder show their skepticism of Enlightenment’s architectural touchstone, the public institution; which they recast as an oversized void, unearthly and mystical. In the future, when people possess transcendent, bionic brainpower, architecture’s thralldom will no doubt be limited to its ability to cow with scale. Vast, inestimable emptiness, not plenitude, will impress.

Further rhetoric lies within the general purview of the project. The fact that the Kunsthalle – traditionally a smaller, collectionless exhibition space – is inflated to more than thirteen times the volume of the current largest building in the world (the Boeing plant in Everett, Washington), expresses a snide observation on the premium put on architecture as a provider of spectacle to both create and validate public spaces. Today, Times Square in New York can barely be understood as public space in any traditional sense, but rather as a condensation of profligate distractions that begets ever more amplified, competing versions that vie for our fragmented attention. The Kunsthallen provide ‘space,’ which is ‘public,’ but its usefulness as public space, as such, is nulled by the building’s humbling dimensions. Standing across the long-length of the building (just under a kilometer), people will look no bigger than peppercorns. These people, I imagine, are the same ones seen milling about on the banks of the Rhine in the Düsseldorf image. They look like all the stock-image people one finds populating computer generated architectural renderings: a carefree, leisurely class, a people who truly enjoy and fully utilize public space, native to nowhere except the collaged reality of architectural renderings. For Miessen and Pflugfelder, architectural reality, vis-à-vis city planning’s perennially stilted bureaucracy, is never projected so much as imagined; hoped.

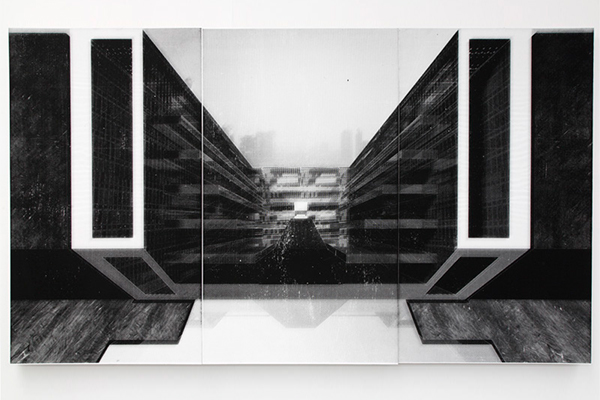

The clearing of architecture’s socio-political register for a fictional one is made explicit in Miessen and Pflugfelder’s axonometric drawing of the Kunsthallen. While theorists like Manfredo Tafuri were claiming that architecture’s striving for formal autonomy transpired from its ‘guilty’ relationship with rationalist-capitalism, many practicing architects since the late 1960s used the axonomeric projection to present form free from its socio-political context, to allow for architectural typology and urban morphology’s self-produced traditions to delimit disciplinary contours. Axons – a projection where the dimensions of each edge are scaled equally, unlike perspectives – are understood to be more truthful in that they show a universal rather than subjective view. In Miessen and Pflugfelder’s drawing, the Kunstalle’s form similarly functions free from its contextual confines; the drawing references neither Dubai nor Düsseldorf as actual places. The Kunsthalle’s constituent parts – terraces, shell, base, roof and art object – are exploded, revealing new correspondences between an otherwise fixed set of relations. The roof-plate figure – a shape that is never really experienced by the visitors – gains a higher symbolic status as a kind of architectonic organizer; its beveled outline serving as the drawing’s borders. Superimposing the axon over the plan, ghosting the forms in a lighter line-weight to show transposition, and ‘gridding’ the drawing to give it its own order, Miessen and Pflugfelder’s drawing parodies a style of hand-done, pen-on-Mylar drawings from an era of exploratory drawing practices between the 1970s and early 1990s – a time when many prominent architects devoted time to theory and philosophy, and found it beneath them to actually build buildings.

The power of Kunsthalle Dubai Düsseldorf lies not in its critique of past practices, but in its ability to propel a critique of architecture and its tools as a practice of the past, itself a historical form. For what Gandy suggested by representing the Bank of England as a ruin, Miessen and Pflugfelder expand by giving a future history to buildings that were never meant to be built. Like Gandy’s bank, Miessen and Pflugfelder’s buildings are voiced, so to speak, in the hazily clairvoyant future perfect continuous tense: the Kunsthallen will have been built to mark the diplomatic unification of two places that jointly renounce art. Architecture’s stability is unseated by this simple conjugation, and it gives the effect of propping a distorted mirror to that which we have eternally held to be solid.

Then again, perhaps the image is unsettling, not because it is distorted, but because it has become so familiar – like repeating a single word many times until it loses all semantic sense. The moment the diverse and dirty stuff of art – of culture – is essentialized into a single object, is also the moment society resigns itself of change. It should be mentioned that the art piece in each Kunsthalle is kept inside a reliquary shaped like the combined buildings – a shiny white box (Düsseldorf) atop a shiny black box (Dubai). Presented with a state-approved object of adoration that resembles the state-sanctioned space for said adoration, we find ourselves locked within a shrouded, mediated experience, looped so tightly upon itself that it takes on the self-validating logic of religion. That this process will have been existing in two far-flung locales shows the rather blighted condition that Miessen and Pflugfelder predict for the future of urban design. For architect Michael Sorkin, “urban design, with its single, inflexible formula, is produced for customers – worshippers – rather than citizens.”[i] The mirror Miessen and Pflugfelder props, then, is not distorted but doubled, like the ones found in clothing store dressing rooms that reflect endlessly into darkness.

[i] Michael Sorkin, “The End(s) of Urban Design,” in Urban Design, edited by Alex Krieger and William S. Saunders, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press) 2009 p. 170